Billions of dollars flow into Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) each year, but there are important gaps in our understanding of how these funds are put to use. One interesting area is the location choice of NGOs and the factors that underpin those decisions.

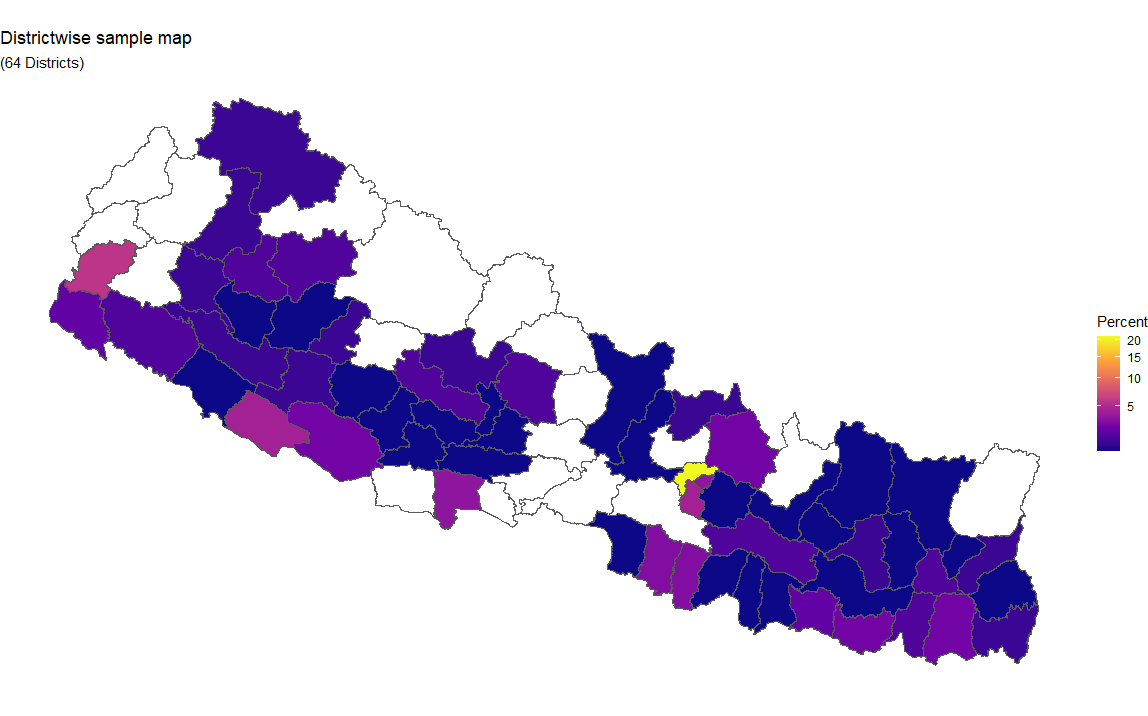

Nepal presents an interesting case study, as it has experienced rapid growth in the number of NGOs in recent years. The total number of NGOs affiliated with the Social Welfare Council (SWC) has quadrupled since the beginning of the century and stands at a little over forty-seven thousand. Among the registered organizations, approximately eleven NGOs exist to serve one thousand people in Kathmandu, while one NGO exists outside the capital city for the same population. This statistic has opened doors for the public and media to openly criticize the NGOs for their love of the valley. But what if we were to forget for a moment Kathmandu exists? Where do the rest of the NGOs go in Nepal? Do these NGOs go to the areas where they are most needed?

I was intrigued by the question and decided to explore the factors that may help us understand where the rest of the NGOs go in Nepal. I further probed the relationship between their official location where they’re registered and the progress of individual districts on the yardstick of development. In other words, were NGOs establishing where development indicators suggested their efforts were “most needed.”

Why do NGOs go where they go?

One may wonder why do we need to know where NGOs go? Before getting into that, let me explain the four typical explanations as to why NGOs establish themselves in any given location.

First, NGOs are viewed as service providers, and therefore they are expected to be close to the population they serve. In other words, NGOs should be located where the community’s needs are higher. This is the most commonly received explanation for location choice, and most of the critics of NGOs in Nepal root their argument here because they feel NGOs are not sited in close proximity to their beneficiaries.

NGOs are also viewed as self-serving. Since these organizations are not self-contained, the key to their survival is the ability to acquire and maintain key resources. Hence, NGOs tend to be in areas where they can meet their needs, be it financial, human resource, or otherwise. And NGOs in Nepal have also been criticized for being ‘resource-oriented’.

Third, NGOs in Nepal tend to be viewed as political agents rather than anything else. The political nexus explanation suggests NGOs in Nepal are started by politicians and these organizations ultimately serve the interests of their political masters.

One additional theory, which I researched in this study, was the idea that NGOs tend to locate in areas where the density of preexisting organizations is high. This clustering could be a consequence of high degrees of social capital, the demand of NGO support from the community, or the availability of resources for the organizations.

Why study NGO location?

Now let us turn to the importance of studying the choice of location for NGOs.

The study of location choice of NGOs offers multiple benefits, including valuable insights for donors and policymakers working in developing countries — like Nepal— to assist in designing their strategies. It can help them understand whether or not NGOs target the most deprived villages and neediest communities. It can also help them secure their legitimacy to appear as valuable partners in the effort to eradicate poverty.

Furthermore, NGO location information could help donors and governments understand the motivation of these organizations, which in turn could help them find and select partners that are better aligned, and design better contracts.

Additionally, NGOs are non-profit organizations that usually depend on the charitable inclinations of their founders and staff. So, one would expect that the factors that affect their location decisions might differ from those that influence commercial institutions, which rely on an explicit evaluation of the present value of future returns and the costs of operating.

What did we learn?

Findings from the study help me conclude NGOs in Nepal are “pragmatic saints”. These organizations grapple with the pressure to secure and sustain resources for their own organizations, while they are being charitable. Findings indicate NGOs serving outside the valley are considerate of the needs of the population they serve. At least one measure of the need of the district appeared significant throughout the study.

I also find strong evidence that access to potential human resources for the organization and access to capital goods and services affects the location of NGOs. Areas with better access to services had a greater density of NGOs. Furthermore, I find NGOs in Nepal are an urban phenomenon suggesting the importance of physical comfort and easy access to resources for people working in NGOs.

I also find the level of political engagement influences the density of NGOs in a locality. Areas with a higher number of members of parliament and better voter turnout ratios had higher numbers of NGOs. This relationship between the density of NGOs and higher voter turnout ratios supports the notion that citizens might have chosen NGOs to provide services they were unable to gain through democratic processes at the local level.

While findings also foster the argument put forth by social capital theorists who often argue that citizens choose to organize to collectively voice their concerns, which may take a form like NGOs, it also reinforces the speculation of the inherent NGO and political nexus in Nepal. The idea being that the location of such organizations somehow has been influenced by the politics and political leaders in Nepal.

Finally, I find that districts with a higher number of preexisting NGOs sees a higher density of new NGOs. Despite the competition for resources, establishing a NGO in areas with existing organizations helps new organizations navigate their way to resources. The clustering also explains the nature of organizations. NGOs in Nepal are mostly clustered in the smaller cities of the country partly that is where the people who are capable enough to start the organization reside.

What do the findings mean for donors and NGOs?

Donors and funding agencies need to work hard on their current funding modality and create a system where NGOs that work in distant locations can access funding and other resources easily. This situation will not be created until and unless NGO practitioners identify the concise needs of the communities and the real issues they intend to solve.

While the study provides a comprehensive picture of the location choice of NGOs in Nepal, it does not provide the answer to the questions relating to their effectiveness. Readers should be cautious as location choice should not be misunderstood for their effectiveness. Whether or not NGOs have been effective in achieving what they assume to achieve by being in their current location, or whether a different location might help them better achieve those aims, remains largely unanswered. Further investigation is required to answer such questions.

This article is an excerpt from the research paper published in VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. The full paper can be accessed at bit.ly/ngolocation